Let's talk about that gay hockey show

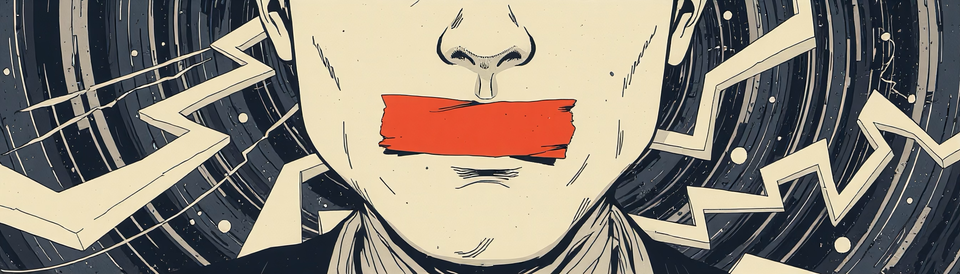

In a perfect world, sexuality would be irrelevant and straight people could do gay roles without issue or judgement — but the reverse is not the case, and in many professional realms someone coming out as queer is detrimental to their careers.

(This post contains obvious spoilers for Heated Rivalry, in case this catches anybody off-guard.)

Unless you've been under a rock lately, you've undoubtedly heard of the six-episode Canadian series about a gaggle of closeted hockey players navigating their private sexuality with their public projections of being heterosexual men. This isn't a review of it, per se, though if I were to give one I'd say that for all I heard about how relentlessly smutty it was, there were raunchier sex scenes in Queer as Folk over twenty years ago and I generally found much of the show extremely cliched, implausibly written, with pacing that made little to no sense (the six episodes take place over nearly a decade, somehow, which means that there are time-jumps of literal years within minutes of on-screen footage) — Jacob Tierney, the writer and creator of the show, was one of the co-writers on an absolutely brilliant Canadian series called Letterkenny, so I'm a little surprised by how sloppy the whole thing was. It's subsequently been revealed that it was an extremely low-budget production shot over the course of a month before HBO caught wind of the buzz and swooped in to give it broader exposure; this is being held up in an underdog sort of way but mostly I would say "it shows." It was shlocky and some episodes literally had me audibly groaning out loud (and not in a good way) — I am admittedly holding it to a higher standard than I think it intended to be, but there's so little queer media on the whole so it feels like a missed opportunity when it's not particularly great. Still, the last two episodes in particular redeemed it a bit further and I'd give another season a watch to see how it fares with more intentionality behind the writing and production instead of "we did not expect this to blow up the way it did." It shows.

Anyway, my not-review aside, I want to talk about something else that came up during the early marketing of the show — particularly around the real-life sexuality of the two main actors in the series, Hudson Williams and Connor Storrie. In an early interview with Jacob Tierney (himself one of the only two queer people headlining the show) and the two leads, Tierney shut down a journalist who asked about the sexualities of the main actors. My initial response was "oh yeah, sure," but after thinking about it for half a second I think dismissing this line of questioning is a disservice in and of itself.

Whether straight people are allowed to do queer roles is a perennial question and nothing remotely new, and there are advocates on either side of the argument. What I find particularly irritating in the case of Heated Rivalry, however, is that the "are they really gay in real life" question was a central part of the viral marketing that both actors — and showrunners — happily capitalised on around the show's release, so acting like it's an irrelevant question when everyone involved was happy to gay bait for attention is a little ridiculous to me.

In a perfect world, this would be irrelevant and straight people could do gay roles without issue or judgement — but the reverse is not the case, and in many professional realms someone coming out as queer is detrimental to their careers.

I mean, this is the central conceit of Heated Rivalry itself and why the three main characters, all of whom are queer, keep it to themselves for fear of losing their jobs if anyone finds out about their relationships with other men — coming out will destroy them and has to be kept a secret.

Straight actors can get Oscar nominations for playing queer roles while queer people are still often relegated to only the sassy best friend who fixes the straight main character's life, like some literal fairy-godhomo.

François Arnauld, himself openly bisexual, plays the character of Scott Hunter who comes out dramatically in episode five of the show. Scott Hunter had secretly been in a relationship with an out gay man, Kip Grady, who finally ended things after being unwilling to continue lying to friends and family to protect Scott's closeted secret. This is a reality that many queer people have lived experience about, both as the one begging their loved one to keep the secret and as the person being forced to do so. For those of us who feel our public identities have been hard-fought, it's an incredibly distressing thing to be asked to go back into the closet for someone else. On the topic of whether or not Hudson Williams and Connor Storrie are gay in real life, Arnauld had a similarly dismissive and reductionist response as Jacob Tierney.

In the season finale, Scott Hunter gives a speech at a ceremony where he accepts a MVP award soon after his public coming out. In that speech, he talks about how living a lie for so long was toxic and damaging to him and the people he cared about and how after going public with his sexuality, he was overwhelmed by the love and support — especially from other people who felt that they could come out as well. François Arnauld has said the same things about coming out openly as bisexual, as has Mitch Brown, who recently came out as the first bisexual man in the AFL's history.

I am genuinely happy for both Williams and Storrie who by all accounts were broadly unknown actors plucked up and thrown into something that became much bigger than anyone was prepared for. I hope this gives them many opportunities in the future and this is just the break they both deserved.

But visibility matters, and visible people bring us closer to a world where it is irrelevant if a straight actor is playing a gay role — because the same opportunities are afforded to queer actors, athletes, professionals, and creatives instead of forcing people to compartmentalise and hide parts of themselves out of fear. Until that day, queerbaiting for viral attention while being unwilling to answer whether or not it's genuine feels very much like trying to have the cake and eat it too.

Comments: